Abstractions & Legibility: Nomenclature

I define legibility as the quality of being easily transferred from one person to another. The most common use of this term is when describing handwriting--legible handwriting is well-formed and clear, such that it is easy to read (and therefore understand). Illegible handwriting, on the other hand, is like a code-- you might be able to make sense of it, but it's going to take a lot more time and work.

This same principle applies to abstractions. Some are so easily understood and obviously true that they are trivial or like nothing at all. They're so deeply embedded in the way that we work, that when trying to talk about them, it's hard to not come off high. "Dude, like I have these thoughts and my hand just like...does them. Where do those even come from? And like what if my blue isn't your blue, but we just call the same things blue--but what you're seeing is like green to me?"

Underlying these questions are serious inquiries into the nature of our experiences--but they often sound ridiculous when you're just trying to make it through the day and pay your mortgage at the end of the month.

On the other end of the spectrum, abstractions can be so illegible that only a few brains can ever approach them. Advanced cryptographic math, quantum mechanics, protein folding algorithms, and transform math are just a few examples of abstractions that describing sufficiently complex topics that they have very low legibility for most people.

There are three major ways to making an abstraction more legible:

- Nomenclature

- Notation

- Progressive Rendering

In this post, lets dig into the ways nomenclature can help (or hurt) legibility.

Nomenclature is the set of names and terms used to describe concepts in a field or area of study. It's the jargon. One of the chief difficulties in learning and using a new abstraction is that most abstractions are actually a constellation of smaller abstractions coming together to describe the overall concept. Before you can think about the "big ideas", you've got get comfortable enough with the little ones such that you can rearrange them without getting totally lost.

This is generally a good bit of work in any field--but it's especially hard in fields which uses poor or unclear naming conventions. There are three major pitfalls in building our nomenclature:

- Irrelevant Names

- Naming Variants & Collisions

- Overloaded Terms

Irrelevant Names

Irrelevant names are names that are so removed from the underlying concept that there's no reinforcement between the words used and the thing itself. This is a huge hurdle for beginners, as it requires them to go through a steep learning curve to be able to participate in any conversation--meaning that the only way to start learning to is focus on memorization for its own sake.

One example of this comes from anatomy, where the field had a habit of using eponyms--names based on the name of the person who first discovered the thing.

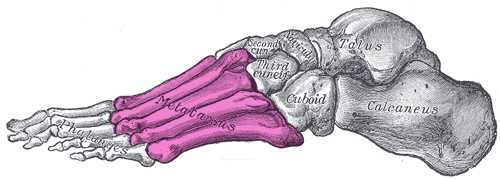

For example, there's a thing called "Wood's muscle". If I asked you where it is, how would you figure that out if you didn't already know? The alternate English name is "abductor of the fifth metatarsal". If you're not a biology major of some kind, that might seem equally opaque--and worse unwieldy. But, with even just a little big of anatomical vocabulary, you can put together exactly where it is:

- abductor - muscles that move limbs away from from their neighboring limbs

- tarsal - a short, angular bone in the ankle

- metatarsal - bones that phalanges and cuboid points (so between your toes and the center of you ankle)

Basically the metatarsals are here:

So the English name--while still requiring some building blocks--allows you to infer the topic of hand from the words. At the very least, you can a more intelligent question than "What's Wood's muscle?"

While this might seem like the kind of thing that warrants the world's tiniest violin--it actually is a huge leap forward for legibility. Beginners can now learn a bit, then start following conversations between experts, and learning from those interactions. The knowledge transfer takes on a more organic nature, and that massively accelerates people's ability to learn as new information becomes part of lived experience as opposed to hours of cramming terms.

Reinforcement

A second advantage of good, relevant names is that each time you interact with a concept, it reinforces all aspects of your knowledge.

Maybe you once knew what an abductor was but forgot. Then, you go to the gym and do a whole bunch of clamshells. The next day, your outer hip is sore as hell. You look it up, and you learn that muscle is called your hip abductor (because it moves your legs away from each other).

That experience reinforces your knowledge--abductors move limbs apart--which you can then access when deciphering "abductor of the fifth metatarsal" in a way that "Wood's muscle" just can't match.

There is a discussion now in anatomy to move away from eponyms for anatomical parts--though a lot of it centered around the fact that the namer's were all male. Politics aside using more relevant names should help newcomers absorb anatomy more easily.

Naming Variants & Collisions

Another dimension in good nomenclature is that it avoids naming collisions--i.e. reusing terms in a confusing way--while at the same time avoiding unnecessary variation that makes increases the number of words to track.

Let's switch to an automotive example. Cars have a variety of lights now, used for different purposes:

- Headlights

- Tail lights

- Signal lights

- Fog lights

- High beam lights

- Daytime running lights

- Brake lights

- Hazard lights

- Dome lights

Over the years, car nomenclature has gotten pretty refined (and we're all pretty familiar with cars) so the above is easy enough to follow. However, imagine you were new the idea of cars. It might be a lot to take in, but as long as you were familiar with a few concepts (light, head, tail, brake hazard, etc.) you could decipher this pretty quick and get to learning.

Unnecessary Variation

Let's create a version of the above with unnecessary variation:

- Head lights

- Tail torches

- Signal indicators

- Fog lanterns

- Distance beams

- Safety brights

- Brake glares

- Hazard flares

- Dome lamps

Just reading the list takes more work--and you know exactly what these are all referring to (and the concepts aren't very unfamiliar). Can you imagine this same set up in a complex, abstract area that you're just learning?

Collisions

Let's create another set of terms, but this time with lots of collisions:

- Head lights

- Rear lights (for visibility)

- Rear lights (for turning)

- Head lights (for low visibility conditions)

- Head lights (for really dark roads)

- Head lights (for daytime use, vehicle visibility)

- Rear lights (for deceleration indicators)

- Rear lights (for hazards)

- Internal lights

The above list is useless without the stuff in parentheses.

Worse, people will likely come up with their own shorthands, leading to an explosion of variations--which they probably won't discuss thoroughly. You quickly end up in an area where someone talks about "indicators" (meaning signal lights), with the person they're talking to nodding along (thinking the conversation is about brake lights), and nobody being able to understand the confusion that results.

Overloaded Terms

Overloaded terms are words that have such a strong associative meaning that no one can separate them from that context. Examples in this area usually dive straight into various minefields: religion, politics, racism (or other derogatory terms), etc. After all, these are the topics that have the most emotional power.

There are different standards for "overloaded" here. When worrying about overloaded terms, it's all about context--overloaded for who?

The internal standard is that the terms shouldn't be distracting or get you in trouble if the contents of your email were linked. For example, you can "redline" a contract--and that's totally fine for an internal term. However, there may have been something specific in the company (or a specific individual) experience that makes that term unacceptable. If you're developing nomenclature, you need to be aware of these things--to the extent possible--and sensitive the objections when something you missed arises.

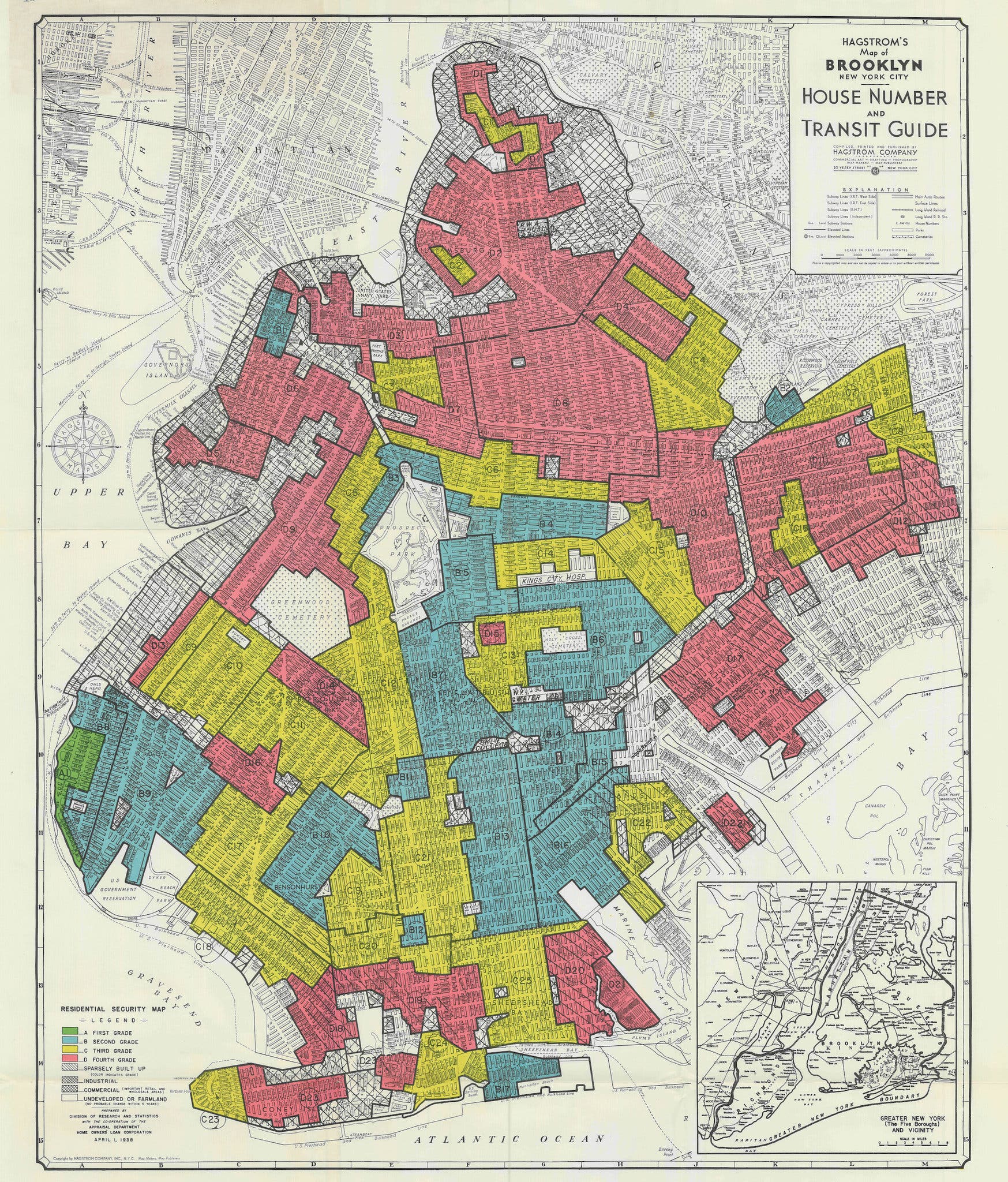

External communications set a higher bar, and you can easily get blindsided by connotations you never even knew about. The term "redlining" has come to mean any sort of racial discrimination in housing, due its history.

Government maps actually visualized zone where black people lived, which became the basis for denying mortgage and other discrimination:

Now, the association isn't so strong as to make people stop using the term "redlining" to refer to other activities (like marking up a contract with changes in Word--which literally marks up the contract with red lines). However, you probably don't want to brand any of your services that way (especially in housing).

Worse, "I didn't know" isn't a defense that works in external arenas. With internal teams, where you have real relationship, apologizing and changing the term will get you out of 99% of problems. But public opinion isn't usually so forgiving. That's one of the reasons that large companies spend so much money coming up with such bland terms.

Nomenclature in Practice

All of the above might sound a bit academic, until you realize that your work probably involves at least some amount of developing nomenclature (and all of you work requires you to learn and use nomenclature developed by others).

Trading Example

Trading nomenclature is the worst. It's basically non-existent for the most important set of things to name: trading strategies.

The ones that do exist are incredibly opaque, and any you get in to a discussion about the nature of the strategy, you fall into a rabbit-hole of jargon that spans medieval Japanese charting techniques, data science, probability theory, a large array of technical analysis chart patterns, financial analysis, and more.

I think this is probably the single largest hurdle for new (and maybe even just all) traders. You get tons and tons of viewpoints declaring the "right thing to do" or criticizing other people's strategies for failing to meet "really important criteria X", for example too low a Sharpe ratio (but wait! maybe the Sortino ratio is the better measure? Or the pain-to-gain ratio?)

I find that the vast majority of these discussions are going in circles because people are talking about executing totally different procedures--but talking as if they're doing the same thing.

Listening to traders debate is like this: Imagine you're sitting a bar, listening to two surgeons debate about how their the surgeries they have scheduled for tomorrow. Both are giving each other strong advice about how to go about it. It's heated, there's a ton of jargon going back and forth--and they both talk with the force of conviction. After doing this for half an hour, you step in and ask, "Geez, you both are sure going at it--hope you're learning a ton. What procedures do you have scheduled tomorrow"?

"Full knee replacement," the first one answers.

"Cardiac valve replacement," the second one replies.

Think of how shocking it would be. While they're both surgeons, they'd effectively have spent that entire time talking past each other because they didn't identify that they were doing radically different things that happen to fall under the field of "surgery"

That's the state of trading today. Nobody has gone through and named all the strategies, and the ones that ones that have been named have opaque names like "Iron Condors" and "Butterflys". It's no wonder--there are millions of possible combinations between timeframes, instruments, risk premiums being harvested, and combination plays.

But trading discussions are very much the worse for it.

Coding Example

Every piece of code ever written is an abstraction expressed in written language. That written language requires you to pick names for things: functions, variables, and constants. Together, the names of these things are the nomenclature of the code.

Imagine if you writing a function to calculate the return of various stocks over the past 10 years. You could use variables like s1, s2, s3, s4--and then good luck figuring out which stock s4 is. Or you could use their ticker symbols.

Sounds easy right? Yet, time and again, developers use inscrutable variables. Or they name things after their favorite nerd cannon. This is the "Frodo server" and it talks to the "Gandalf cluster", which is monitored by "the Eye of Sauron". I was guilty of this myself--in my first startup, we named our servers after Simpson's characters: Bart, Lisa, Homer, etc.

Product Management Example

Good nomenclature in incredibly important when developing products. Product managers are usually the shepards of the nomenclature. They map out user flows, features, navigation, and user communications. As part of all this, they need to name absolutely everything so the internal team can communicate efficiently with each other.

Product managers also usually have a much harder job: setting nomenclature for users. This 100x harder for a number of reasons:

- Each user is bringing their own unique history and association for terms

- Training opportunties are limited

- In general, users just don't read your stuff

- You have a very short time to reach them, so simplicity is even more important

- Users don't ask questions when they're confused

- They just bounce, and there can be many reasons for that--so you have to deduce that confusion is the reason

- You can't take advantage of "scoping" to avoid collisions

- For internal terms, it doesn't matter if Apple also uses the same terms you do--everyone knows where they work

- For user-facing terms, good luck to you if your terms collide with Apple's!

- Terms can't just be clear--they also have to be attention-grabbing

- This isn't true for all terms--but for the major brand/product terms, you want convey a certain image, emotion, or positioning at the same time as conveying the actual content

Product managers also usually work with some form of brand team to help with the external-facing terms, but even with the help, good nomenclature is a tough problem to solve!

I'll explore how notation and progressive rendering can improve legibility of abstractions in future posts.